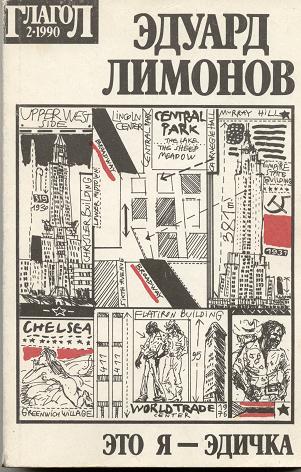

Eduard Limonov, 'It's me, Eddie'

Emigration, eroticism, egoism, erudition, eccentrical, ESTHETICS

'All in all, he was what we call it in Russia, a fucker. Such people become artists so that it was easier to get a woman into bed using a free profession'.

Eddie 'Edichka' got me into bed with this book, and he did it in such a way that you won't want to read anyone else.

So, what is it there, ladies and gentlemen, in this story, which is obviously 18+ but I would recommend it as a manual for teaching feelings, for instance, from the age of 16?

A guide for immigration, the art of stylish poverty, sometimes a satirical journalistic essay about all political movements, and a very romantic novel, to my taste.

The angriest, witty poetry of this prose which can't hide behind rudeness and nudity, even partial nakedness of its characters, can't wash away the poetry by the fluids of their bodies.

'Sex is sex, fuck whoever you want, but why betray my soul?'

Generally speaking, pornographity is limited here, no matter how this phrase may sound, because the book is about love:

Love and tenderness towards women, which hides behind the hatred towards the Woman.

The nominal plot thread which links the walk of tanned Edichka through 300 streets of New York — the separation from his wife, the wonderful Elena, and a wish to kill, take vengeance, crush — no matter her or himself.

But it's precisely the Woman who made a poet out of a man.

'Squirrel, silly little thing, bitch' — almost Chekhov's rhetoric in relation to the beloved one; these unique sweetnesses, inapplicable to anybody else.

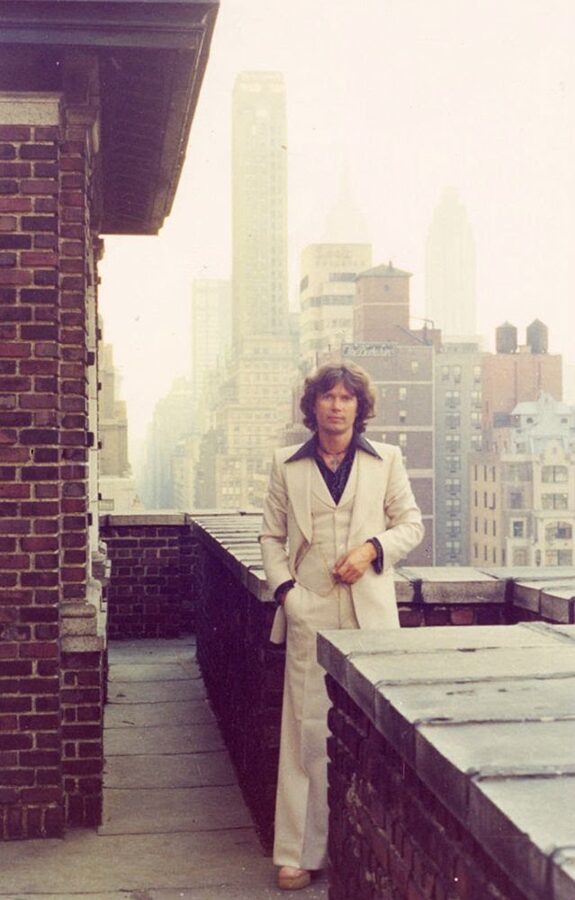

Self-love on the verge of boasting helps to overcome both embarrassment and disgust at all the unbearableness of being — when you are so young and beautiful, is it worth worrying about hugging a tramp in a musty back street?

The descriptions of attire, that importance which a man who usually loves playing with words, playing with the reader, attributes to the description of his clothes —from chapter to chapter, 'an amazing white waistcoat', a black handkerchief, shoes— is almost Nabokov's self-admiration (in diaries, that one could dedicate pages to the descriptions of his outfit up to the colour of his socks).

'…I wore and wear only high heeled shoes, and I ask to put me in the coffin, if there is one, in some incredible shoes and, by all means, high heels' — and how did they put him there, I wonder?

Nobody knows and it will never be known which parts of this are autobiography and which ones are mystification and poetry, but there is the simplest clue from the author — 'what is compared to childhood cannot be a lie' — and this broken glass from his childhood, vodka, Kharkiv, volleyball, is it all real? All that which comes out on night shifts as a waiter in a hotel o while drinking brandy during his breaks as a loader?

Nagging, very very arrogant sense of not belonging, otherness: the unwillingness to be a Russian martyr in a strange land, nor an intellectual journalist in an emigrant newspaper, nor left-wing, nor right-wing, nor rich, nor businesslike — just love.

And finally — the descriptions of a hangover (what do you think we are all here for) — oh, how good are these descriptions in the chapter about Rosanna!..

Imagine right now the worst hangover you have had, and then imagine that you are doing a full thorough cleaning in a state of hangover in the flat where you had been having fun all night — and in the process you get cheap and warm pink wine from a big bottle to recover, not good chilled Spanish dry one.

In short, if Bataille, Nabokov and Bukovski had organized a literary group sex and invited Erofeev and Dovlatov to look at it, the result would have been Limonov's prose, and he actually made up everything for them in terms of sensuality.

This book is definitely on the list of my favourites and will never disappear from it.

Who will like it: those who didn't get scared but got attracted by this feedback.

What to drink: oh. Probably cold, cold, even icy vodka, and all of a sudden in the morning (but only if you didn't spend the night at home, and no more than two shots).

Author: Ksenia Yakovleva Telegram bookswine